Lesson Outline

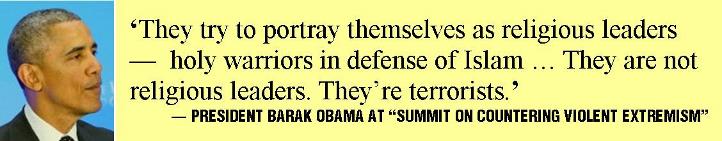

As the White House hosted its February 2015 summit on the multinational clash with the militant group that calls itself the Islamic State, President Barack Obama found himself in a war of words — or, to be more precise — a war about words. His critics, largely from the political right, took issue with the president’s reluctance to identify the “violent extremism” targeted by the summit as “Islamic terrorism.” Meanwhile, another war about words was sparked by news coverage of the murder of three Muslims in Chapel Hill, N.C., and the perception of a double standard involving the use of the word “terrorist.”

The questions raised by these events and their coverage pose challenges for both news organizations and news consumers because like a firearm, language can be loaded. News Literacy teaches us that the words journalists choose can make all the difference as news consumers try to separate news from opinion. Here are three factors news consumers should consider:

.

1. BEWARE OF LOADED LANGUAGE

The most heated political and social debates are replete with words and phrases that carry assumptions and communicate a point of view. Describing a proposal as a “reform” implies it’s a positive step, which may be a matter of debate. Calling abortion opponents “right-to-life advocates” adopts the language of their side of the debate. The same goes for using the pejorative term “illegal alien” in a news story about the immigration debate.

That’s why news organizations that strive for impartial reporting free of opinion adopt editorial guidelines that promote the use of neutral language. In many cases, it’s the difference between describing and characterizing — a distinction that’s at the heart of the BBC’s editorial guidelines on use of the word “terrorist.”

Terrorism is a difficult and emotive subject with significant political overtones and care is required in the use of language that carries value judgments. We try to avoid the use of the term "terrorist" without attribution … We should use words which specifically describe the perpetrator such as "bomber," "attacker," "gunman," "kidnapper," "insurgent" and "militant." We should not adopt other people's language as our own; our responsibility is to remain objective and report in ways that enable our audiences to make their own assessments about who is doing what to whom.

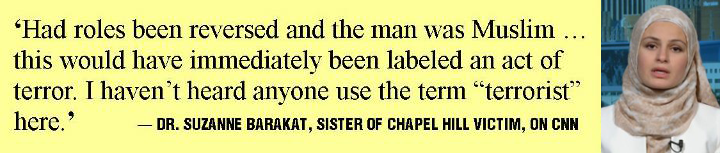

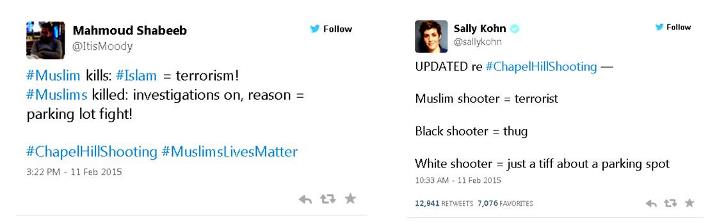

Coverage of the Feb. 10 murder of three Muslims in Chapel Hill, N.C., has drawn criticism of U.S. media outlets by Muslims abroad as well as in America not only because the incident didn’t get as much attention as the Jan. 7 shootings in Paris or the Feb. 15 attacks in Copenhagen by Muslim gunmen, but because the European incidents were immediately characterized as terrorism. In Chapel Hill, police quickly embraced the theory that the gunman, a vocal critic of religion on Facebook, had been motivated by a parking dispute.

Who is and isn’t a terrorist? Determining that an attack like the destruction of the World Trade Center towers was an act of terror is straightforward enough. Labeling a group a terrorist organization, though, can be a political determination -- a matter of opinion that depends on whom you ask — and when. Hamas, the Palestinian organization running Gaza, had a powerful ally in Cairo while Egypt was led by a president from the affiliated Muslim Brotherhood. The government that took its place has a very different opinion of Hamas, and on Feb. 28, an Egyptian court declared Hamas a terrorist organization.

.

2. PAY ATTENTION TO WHO IS TALKING

Another important distinction can be found at the heart of the BBC’s caution against using the term terrorist “without attribution.” If loaded language is being used or a subjective characterization is being made in a news story, journalists need to be clear about who is making it. That happens through “attribution” — the practice of explicitly identifying the source of an assertion. The goal, of course, is to preserve impartiality by making clear who is accountable for the characterization.

It’s one thing for the district attorney to call a suspect a murderer, and another thing entirely for the anchor of a news broadcast to do so without attribution — a clear indication of opinion.

When an impasse between congressional Democrats and Republicans shut down nonessential government operations in the fall of 2013, the Fox News channel’s website blurred the line between news and opinion when it began calling it the “government slimdown.” Its editors even inserted the phrase in Associated Press stories, replacing all references to the “government shutdown.” The obvious partisanship the loaded language revealed made Fox the target of Comedy Central’s Stephen Colbert, among others.

.

3. THE AUDIENCE HAS AN IMPACT

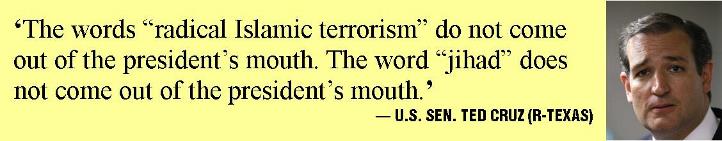

“Leading up to this summit, there’s been a fair amount of debate in the press and among pundits about the words we use to describe and frame this challenge,” President Obama said at the conclusion of the White House Summit on Confronting Violent Extremism. “So I want to be very clear about how I see it. "al-Qaida and ISIL and groups like it are desperate for legitimacy … We must never accept the premise that they put forward, because it is a lie.”

News Literacy teaches us that news judgment is influenced by a news outlet’s understanding of its audience, and the same may be said of political leaders trying to draw on the power of words to mold opinions. Sen. Cruz, a likely GOP presidential candidate, has to be conscious of his party’s base and its longstanding contention that the president is soft on terrorism. President Obama, on the other hand, has to be aware of the impact his remarks can have not only on American Muslims but also on the fragile coalition of Middle Eastern countries fighting the Islamic State group. One of the realities of the Internet age is that leaders are no longer able to tailor one set of remarks for domestic consumption and another for a global audience.

“Words like ‘jihad’ and ‘Islam’ have a huge authority in the Muslim world,” New York Times national security correspondent Scott Shane explained on NPR’s “On the Media.” “And to hand those labels over to al-Qaida or to ISIS, to affirm that what they call a jihad is, in fact, a jihad in religious terms would be a real problem – and that’s why the Obama White House has been very careful not to say that … A lot of counterterrorism folk, they say you’re in a war of ideas, a battle of ideas, and you certainly don’t want to suggest that al-Qaida and ISIS are Islam. You want to treat them as a murderous criminal offshoot that falsely claims the cloak of religion.” (That’s also why news organizations routinely refer to “the self-described” or “so-called” Islamic State, referring to the group in a way that avoids legitimizing its religious claims.)

When religion and politics mix and partisans can’t even agree on the language of the debate, news organizations striving for impartial coverage face the challenge of finding neutral language and making sure words chosen to appeal to a specific audience are always attributed to the person using them.

The line between news and opinion also blurs sometimes when a news outlet adopts the perspectives and, in some cases, the biases of its audience.

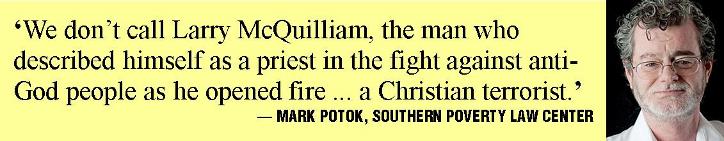

Mark Potok of the Southern Poverty Law Center told NPR’s “On the Media” that there’s a natural tendency “to think of terrorists as people who don’t look like us or think like us or worship like us.” In Austin, Texas, on the Friday after Thanksgiving last year, Larry McQuilliam fired more than 100 rounds from an assault rifle at government buildings and the Mexican consulate before he was shot and killed by police. “His actions were explicitly based on his bizarre reading of the Bible,” said Potok, whose center tracks the activities of right-wing domestic terror groups.

No one suggested in the media that the shooter’s actions were representative of Christianity, nor were Christian groups asked to condemn his actions.

.

The Take-away for News Consumers.

Look out for loaded language as you try to separate news from opinion. Pay attention to whose words they are and who is using them. Compare the language used in news and opinion articles on the same topic and in coverage directed at different audiences.

And watch out for assumptions — especially when religion and politics mix.

.

Questions for Classroom Discussion

1. Can you think of some other examples of loaded language and neutral words a news reporter might use instead?

2. Do you agree with the BBC’s guidelines on use of the word “terrorism”?

3. Compare the attacks in Paris, Copenhagen, Chapel Hill and Austin. Should news outlets have declared each of them terrorism? How relevant was the religion of the attackers and victims?

4. Was Fox News cross the line separating news from opinion when it began to refer to the government shutdown as a “slimdown” on its website?

.

Resources

1. The BBC’s Editorial Guidelines on use of the words “terrorism” and “terrorist”

http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/page/guidance-reporting-terrori...

2. “Safe Words” episode on NPR’s “On the Media”

http://www.onthemedia.org/story/safe-words/

3. “Jordanians See U.S. Reporting Bias in Coverage of Student Killings,” New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/14/world/middleeast/online-commenters-see...

4. “Faulted for Avoiding ‘Islamic’ Labels to Describe Terrorism, White House Cites a Strategic Logic,” New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/19/us/politics/faulted-for-avoiding-islam...

.

-

Key Concepts

-

Grade Level

-

0 comments

-

1 save

-

Share